London Victoria

Enter the East Kent Railway

A House of Commons Report of 22nd May 1855 stated that ‘’the impatience of the

gentlemen of the county of Kent’’ had led to the application for the

construction of a 48½-mile railway between Canterbury and Strood. The ‘’East

Kent Railway Act’’ was passed on 4th August 1853, and capital for the line was

organised as follows:

One individual in London was wholly responsible to provide £100,000 (£6,521,700 at 2007 prices)

A stock-broking firm was committed to £80,000 (£5,217,360 at 2007 prices)

The railway’s building contractor was to supply a further £72,000 (£4,695,625 at 2007 prices)

£253,500 (£16,532,515 at 2007 prices) in the form of shares and loans

The ‘’impatient gentlemen’’ were wealthy businessmen of Faversham. Having watched the SER construct a ‘’Weald of Kent’’ trunk line to Dover, in addition to witnessing the same company failing to extend its North Kent Line over the Medway to Rochester and Chatham, the group found its home town deprived of a vital railway link to the capital. In the same Parliamentary Report of 22nd May 1855, it had been made clear to the promoters that the proposed line would only be of use if it was extended to Dover (or, as it was then known, ‘’Dovor’’), thus providing a direct link between London and the Channel Port. As a result, an extension from Canterbury to Dover was authorised in that year, but things were already going awry in the East Kent Railway (EKR) camp. Parliament had noted, again in 1855, that the promoters of the EKR had adhered to not one of the conditions of the 1853 Act. It was also at this time that the company – already beset with money problems – came crawling to Parliament, requesting financial assistance, enabling it to complete the railway bridge over the River Medway. At this time, it was customary for the Government to impound 10% of the total capital assigned to a railway project, to guarantee the bona fides of the undertaking and that of its promoters. The money was deposited with the Court of Chancery, and for the EKR project, £50,550 was held. The Admiralty had also applied to Parliament for the money to be released, for it was also interested in seeing the completion of the railway bridge over the Medway. Opening of the EKR was piecemeal:

Chatham to Faversham: 25th January 1858

Chatham to Strood: 29th March 1859

Faversham to Canterbury: 9th July 1860

Eastward extensions to Thanet had also been commissioned, and although covered extensively in other sections of the website, it is worthy repeating opening dates, if only for the sake of completeness:

Whitstable to Herne Bay: 13th July 1861

Canterbury to Dover: 22nd July 1861

Herne Bay to Ramsgate: 5th October 1863

The EKR had its

sights set on the proposed West End terminus of the VS&PR, and to get there, the

company intended running over the SER’s 1849-opened North Kent Line, which in

turn could provide access to the metals of the WEL&CPR and, ultimately, the

station of the VS&PR. The EKR failed to acquire running powers over the North

Kent Line: the SER had countered such proposals, claiming that the route was

already running at full capacity and was unable to accommodate more traffic,

neither its own nor that of another company. As a result, the EKR was authorised

to forge an independent route to the capital, and in light of this, the company

was renamed the ‘’London Chatham & Dover Railway’’ on 1st August 1859.

Bridging the Gap

The Victoria Bridge (or, alternatively, Grosvenor Bridge) was the first to carry

a railway across the Thames. In September 1858, work commenced on dredging the

gravel from the site of the proposed river piers, and on the 10th October of the

same year, piling of the cofferdams and gantries began. Cofferdams were

temporary watertight enclosures which could be pumped dry to permit construction

to take place under standard dry conditions. Three piers would eventually span

the Thames, and the first stone was laid on the northern of these on 9th June

1859. Erection of ironwork began on 28th February 1860, and the bridge was a

product of John Fowler, the VS&PR’s Engineer in Chief, and William Wilson, the

Assistant Engineer. The building contractor was Mr Kelk, who was also

responsible for the construction of both Victoria terminus stations and the

Grosvenor Hotel.

The bridge cost a total of £90,000 to build, equating to £3.00 per square foot.

The quantities of materials used in the construction of the bridge were as

follows:

197,800 cubic feet of timber, used temporarily in gantries and cofferdams; 16,800 cubic feet of this was used in floors

10,700 cubic feet of York landings

4050 cubic yards of concrete

6500 cubic yards of brickwork

23,857 cubic feet of Portland Roach Stone

57,205 cubic feet of Bramley Fall Stone

1296 tons of wrought iron

225 tons of cast iron

The bridge extended

for a total length of 920-feet and comprised two stone abutments on each side of

the river, with three piers within the Thames, all of which supported four

arched spans of 175-feet length each. There were two land openings, one at each

end of the bridge, which had a span of 70-feet and carried the railway above the

roads at a height of 16-feet. Each arch rose up to a peak of 22-feet above

Trinity high water level, and between the latter and the springing of each arch

(i.e. where the arch left the pier) existed a height of 4-feet 6-inches. Thus,

each arch alone measured 17-feet 6-inches from top to bottom.

At the riverbed, the three piers were each 18-feet wide, tapering to 12-feet by

the time the iron framework of the arches was met. Piles for the foundations

were sunk to a depth of 15-feet below the layer of clay in the riverbed (30-feet

below high water level), and cofferdams used to drain water. The foundations of

the river piers were subsequently driven into solid clay to a minimum depth of

8-feet, and a 4-foot-thick concrete bed was laid. The latter was formed by using

one part of Portland Cement to seven parts of clean river gravel. Upon the

concrete were set two layers of Yorkshire Rag Stone, each of which was one-foot

thick, and on top of this was placed a layer of brickwork, set in cement, rising

to a height of 18-inches below the lowest water level. Between the lowest water

level and the springing of the arches, the piers were faced with Portland Roach

Stone, set in lias, a form of limestone. Above the springing of the arches, the

masonry became faced with Bramley Fall Stone, obtained from near Leeds, and this

was used to create various mouldings and ornaments along the bridge.

Each arch comprised six curved ribs of wrought-iron, affixed to cast-iron

bedplates set into the masonry of the bridge piers. Between the parapets of the

bridge existed a width of 32-feet, allowing the structure to accommodate a

double-track line of mixed gauge. The rails were carried at a height of 24½-feet

above Trinity high water level, and the strength of the bridge was tested on 9th

June 1860. This involved placing a locomotive, coupled to fully laden trucks,

upon the bridge, creating a total weight of 350 tons

Terminus: Design and Construction

Worker strike action in autumn 1859 delayed construction work. However, on 28th

February 1860, the directors of the VS&PR declared in ‘’The Times’’ newspaper

that ‘’the works of the line and bridge are now so advanced as to leave no doubt

of their completion by the appointed time’’. The directors had also submitted a

Bill to Parliament for the absorption of the VS&PR by the LB&SCR, with an aim to

dissolve the former by 1st June 1861. By this time, the GWR had come on the

scene, and the company intended operating additional services to Reading and

Windsor from Victoria. GWR services were predominantly Broad Gauge and capacity

at Paddington had already reached saturation point. A circuitous route to

Victoria was to be forged, which would see GWR services twice pass over the

Thames (more of later).

To preserve the exclusiveness of Belgravia and Pimlico, landowners required that

the terminus approaches be covered for half a mile by a light iron glass roof.

Furthermore, to minimize the sound made by passing trains, thick sheets of

vulcanised India rubber had to be laid in-between the rails and the longitudinal

sleepers. Such restrictions prevented an architectural masterpiece being

produced, and particularly from the entrance façade, the terminus eventually

looked like a hotchpotch of temporary structures. The ‘’Brighton’’ station was

designed by Robert Jacomb Hood, engineer of the LB&SCR, and comprised a

ridge-and-furrow roof, supported upon a brick wall to the west and two rows of

iron columns to the east, covering a dozen platforms and ten tracks. The station

comprised 10,400 square yards of departure platform and 4,450 square yards of

arrival platform, and the total capital made available for the construction of

the terminus had been £676,000 (about £49,500,000 at 2007 prices). It was

1000-feet in length and 480-feet at its widest point, and covered an area of

about eleven acres. The trainshed rose up to an unimposing height of 40-feet,

formed of sixteen spans of 50-foot width and 230-foot length. Waiting rooms and

booking offices were erected at the head of the station, beyond the buffer

stops, and separate platforms (about two feet above rail level) and offices were

provided exclusively for Crystal Palace traffic, to alleviate overcrowding. The

station’s northern façade comprised a pair of canopies: the larger of the two

measured 100-feet in length by 40-feet in depth, and was constituted of a trio

of rectangular sections. The second, smaller canopy was positioned to the west

of its larger counterpart, and measured about 65-feet in length by 35-feet in

depth.

The Brighton station formally opened to traffic on 1st October 1860. Closure of

the Pimlico terminus, south of the Thames in Battersea, had occurred on 30th

September 1860, but at this stage, the LC&DR had yet to get beyond Strood. This

it finally did when through running between Canterbury and Victoria commenced on

3rd December of the same year, but the company still lacked a proper terminus,

instead using temporary accommodation for 1½-years. LC&DR metals extended only

as far as St Mary Cray; between here and Shortlands (then known as ‘’Bromley’’),

the company ran over the rails of the Mid-Kent Railway, which at this time was

leased to the SER. These in turn led to the network of the WEL&CPR which,

naturally, provided access to Victoria: the route into London was a circuitous

one. Furthermore, the WEL&CRP had been absorbed by the LB&SCR on 1st July 1859,

thus the LC&DR found itself at the mercy of its neighbour at Victoria, and was

subject to access tolls. Problems soon arose with regards to train priority and

track usage, resulting in the LC&DR forging a completely independent route to

the West End terminus (more of later).

On 25th August 1862, the ‘’Chatham’’ station was deemed formally complete.

Compared with its ‘’Brighton’’ neighbour, it was somewhat more attractive,

solely as a result of a graceful trainshed. The station was designed under the

guidance of the VS&PR’s Consultant Engineer, John Fowler (Knighted in 1885). The

building contractor was one Mr Kelk, and the terminus was subsequently leased

jointly to the LC&DR and GWR. The lease was for a period of 999 years, and as

part of the agreement, none of the railway companies were required to pay tolls

to the VS&PR for use of the line over Grosvenor Bridge. The LC&DR was subject to

an annual rent of £32,000 at Victoria, and the GWR paid £18,000 per annum.

The pride of the site was indeed the aforementioned trainshed, which comprised

two arched spans of varying dimensions: the western span was the larger of the

two, measuring 129-feet by 385-feet, whilst its eastern counterpart measured

127-feet by 455-feet. The spans comprised an iron framework held together by tie

rods, and running along the eastern elevation of the trainshed were yellow-brick

offices, lined with Portland Stone, which were built to a height which met the

underhang of the eastern arched span. However, at the northern façade of the

‘’Chatham’’ station, it was the same old story. As per the ‘’Brighton’’ station,

passengers approaching the ‘’Chatham’’ site were presented with a hotchpotch of

single-storey structures, in the form of clapboard offices. As touched upon

earlier, residents of Pimlico had imposed severe restrictions on the railway,

which prevented any architectural extravagance. Perhaps as a consolation, the

twin-arches of the ‘’Chatham’’ trainshed could still be appreciated from the

north, as a result of single-storey timber façade structures. Whilst the two

termini stood side by side, there was no access between the two inside: they

were essentially two wholly separate stations.

Straddling the approaches of the two termini was Ecclestone Bridge. This carried

Belgrave Road over the tracks, and extended for a length of 235-feet. The bridge

comprised wrought-iron girders suspended upon a series of pillars, the latter

arranged in a fashion to provide five openings underneath. From the buffer stops

of the termini, the line followed the course of Grosvenor Canal, thus the rails

were virtually level. The line began to climb steeply on the approaches to

Grosvenor Bridge, at a gradient of 1 in 64. On the south side of the bridge, the

line descended at a rate of 1 in 60.

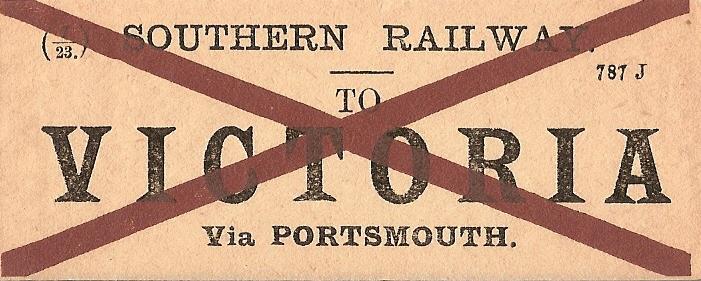

A Southern Railway luggage label combines both the red cross of the LB&SCR (indicating it has come from the

Isle of Wight), and the ex-LSWR's ''787'' stock code. Raymond Fuell

1976

Victoria ''Eastern'' box formerly stood overlooking the southern ends of platforms 1 and 2. It was opened under

SE&CR auspices on 4th January 1920 as Victoria ''A'' Box, and boasted 200 pneumatic pull-out slides. It was

built to an in-house SE&CR design based heavily on those earlier Saxby & Farmer products of the previous

century. This same design was later continued by the Southern Railway for construction of new signal boxes

at Ramsgate and Aylesford. Victoria Eastern cabin went out of use on 13th May 1979, when control was

temporarily transferred to the 1939-opened signal box which controlled the ''Brighton'' platforms. The entire

terminus subsequently came under the control of the ''Victoria Panel'', based at Clapham Junction, on 9th

May 1980. The triangular shadows seen here are those of the Central Division station's trainshed.

© Roger Goodrum

1977

Unrefurbished 4 CEP units are the order of the day in this view of the Eastern Section platforms, which also

includes the full extent of the Central Section trainshed, before any redevelopment work commenced. On the

left is 4 CEP No. 7169, forming a boat train service to Folkestone Harbour, via Orpington, whilst on the right

is recently-arrived 4 CEP No. 7163. © David Glasspool Collection

1977

British Rail luggage trolleys abound on platform Nos. 1 and 2, as 4 CEP No. 7197 disappears underneath

Elizabeth Bridge. Notice on the left, above the roof of the stabled 4 CEP, the top of the ex-SE&CR signal

box. © David Glasspool Collection

<<Previous Next: the History Continues >>

Return to the Kent Rail Homepage or alternatively, check for Updates.

Website & Copyright information - Links - Contact the Webmaster

All content is copyright © David Glasspool unless otherwise stated